“I Would Definitely Go Back”

A conversation with Nigerian immigrant Dorcas Eunice Tornwini

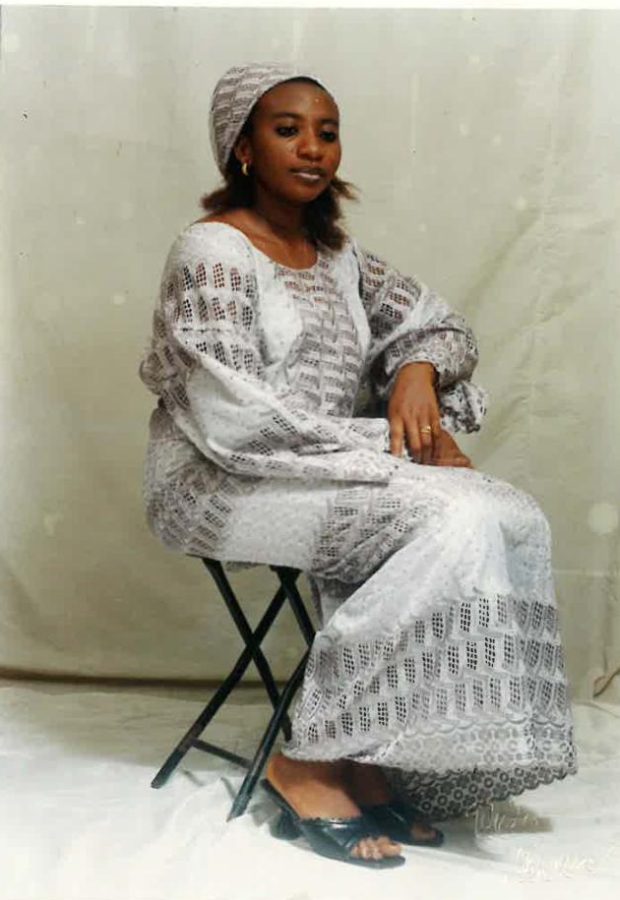

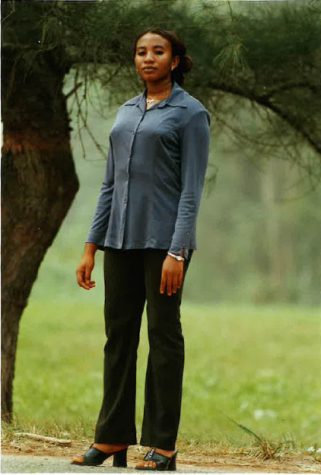

Dorcas Eunice Tornwini

April 20, 2023

“Seahorse Stories” is an ongoing collaboration between the Register and 9th grade English teachers that aims to share more stories from our BHS community in their own words.

My mother is named Dorcas Eunice Tornwini. She was born in the late 1970’s. My mother is from Akwa Ibom State with a population of 5.4 million people in Southern Nigeria. She is the youngest of 5. My father immigrated to America in 1999 and my mother immigrated in 2003. Obviously living in Burlington, Vermont (of all places) was a big shift for her. Some examples of change were with schooling. Before my mother came to Vermont she was attending University in Nigeria. But because she moved here, her credits did not transfer. So she has had to balance college classes, a job and raising 3 kids. She also actively holds on to her Nigerian identity and doesn’t let it get washed away. She does this with the way she raises her children, filling her home with traditional food, music and beliefs from Akwa Ibom (the state in the south of Nigeria where she is from).

Q: Why did you leave Nigeria?

A: We left due to a crisis with the government – so we had to flee. The government was ruling like a dictatorship and it wasn’t safe. The government was retaliating with force against people who didn’t want to support the government. They killed and vandalized people’s properties.

Q: Can you describe moments when you feel you were able to hold on to your culture while living in a predominantly white area?

A: I cook the same food that I eat in Nigeria. I listen to music: Sinach, Davido, Steve Crown, etc. I keep in touch with my family back home. I have traditional clothing as well.

Q: Have you ever felt that your culture has been pushed aside?

A: I mostly just try to keep my head down and mind my own business so that they don’t know my culture and it can’t get pushed aside. I know who I am, so that’s all that matters. I respect the white culture. I try to not let living in Vermont diminish my culture. Because it is who I am and who I always will be.

Q: I know that you once told me a story about how you brought traditional food to your previous place of work and a white lady had thrown it in the trash because she said it smelled bad. How did this make you feel?

A: I was sad, but at the same time I try to not let it get to me. The lady that threw away my food was a close-minded person who hasn’t experienced other cultures and living in this area for your whole life can do that.

Q: Can you talk about the shift, language-wise, in Nigeria versus America?

A: At home I spoke Ibibio, but when I got to school I had to speak English because of all the different dialects we have and because of the western influence because of colonization. It was compulsory for children. Some languages in the village you would have to use the local dialect. It was sort of easy for me to understand writing-wise and speaking-wise. The pronunciation was a lot more challenging because I had an accent.

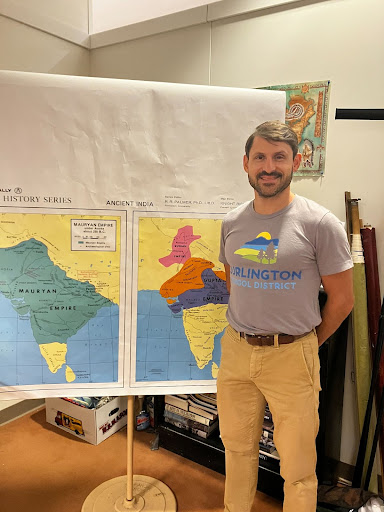

Q: What are a few of the major differences you see in our school system?

A: In my school, if you were late you had to be punished. A punishment would be like you go and cut grass for maybe an hour. You could sweep the teachers office, but you always had a consequence. All the kids knew not to disrespect your elders like the teacher because that is taught from your house. I have taught you and your siblings these similar beliefs like greeting and collecting things with your right hand, respecting your elders and not talking back.

Q: What are the differences in government?

A: The government in Nigeria is a “democracy” but the government tends to oppress the people even though they shouldn’t.

Q: Would you go back in the next couple of years?

A: I would definitely go back