Friends, foes, or food?

Lobster article teaches students critical thinking.

November 1, 2022

A friend of mine interrogated me on the ethics of cooking lobster. She asked, “is cooking lobster ethical?” She was so passionate about this question and kept saying things like “they can feel pain,” “lobstering negatively affects the environment,” etc. I remember thinking: “What a weird question. I’ve eaten lobster before, but I’ve never thought about the process of cooking it.” For a whole week, I kept thinking about this question.

I began asking everyone I know if they thought lobsters are friends, foes, or food?

“I think they’re our enemies, but just because someone is your enemy doesn’t mean they deserve to suffer,” Norah Miller ‘24 said.

One point for foe.

“[Lobsters] are suffering and they’re sentient beings, so they have emotions- they can feel things,” Julia Neubelt ‘24 said. “They’re scary, but I don’t think they should be food either. I think they should just be left alone.”

Two points for foe.

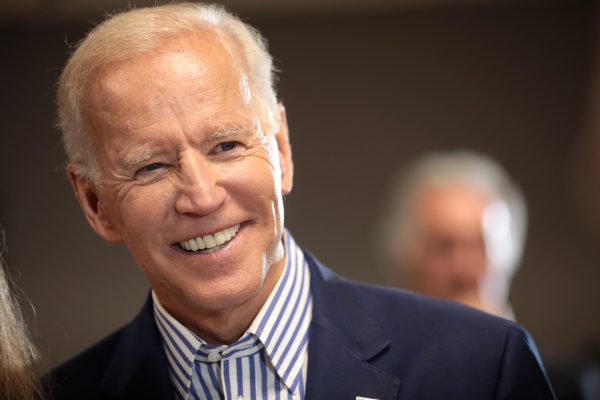

“I think nothing of killing a small insect,” Mr. McConville said. “And I don’t think that lobsters [are an exception]. I think I will continue eating lobster at this point.”

One point for food.

Turns out this question of ethics was posed from the article “Consider the Lobster” by David Foster Wallace, which my friend read in Peter McConville’s Contemporary Literature class. The article follows Wallace who was sent to the Maine Lobster Festival in order to write a travel piece for Gourmet Magazine. Instead of writing about travel, the author wrote a philosophical exploration into the ethics of eating lobsters.

Neubelt and Miller both have different views from McConville. I began to wonder if this was more than just a simple question of whether lobsters are friends, foes, or food. I questioned if this was more about objectivity and critical thinking. I began to wonder about the best ways to teach ethics and morality in a public school.

“My goal is not to convert people to not eating lobster or any other food here,” McConville said. “My real desire is that people walk into the room and go: ‘what the heck was that thing that we just read?’”

Is this way of teaching ethics effective? Reading articles and hoping students will catch the multiple themes and ethical implications? According to Giselle Weybrecht, author and advisor on sustainability at the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business, it is- if the article is relatable.

“Focus on examples of situations that students are likely to find themselves in and give them the opportunity to reflect and discuss what they may do and why, if put in that situation” Weybrecht says. Weybrecht goes on to share more tips on how to teach ethics in her article “How to Teach Students to Be ‘Ethical,” including:

1. Go beyond what is right and wrong and into the reasons and impacts.

2. Challenge your students by adding complexity. In the real world, no decision will be as straightforward as it will be in the classroom.

3. Give students the courage to ask the right questions and the confidence to make what they believe to be the right decisions.

So are lobsters friends, foes or food?

I think it depends on the person you ask. Some people are vegetarian or vegan, some are allergic to seafood and some people just don’t like lobsters; everyone falls into a different boat. For me, lobsters are foes. Maybe my answer doesn’t matter that much. Maybe asking ethical questions and really thinking through my own reasons for my own answer, is a lesson in itself.