Written by Halle Newman

On the morning of August 6, 1945, thirteen-year-old Shigeko Sasamori walked through the streets of Hiroshima, Japan, admiring the sunshine when she noticed an airplane flying overhead.

“The white little grey airplane looked so beautiful in the blue sky,” Sasamori said.

She began to notice “white things” falling from the plane.

Then, “boom”.

On August 6, 1945, the United States dropped the world’s first atomic bomb, named “Little Boy” on the Japanese city of Hiroshima, killing 60,000 to 80,000 instantly. Three days later the U.S. dropped a second atomic bomb named “Fat Man” on the city of Nagasaki, killing about 40,000 instantly. Thousands more died in both cities in the days, months, and years after the bomb was dropped, and many are still suffering today. On August 15, Emperor Hirohito announced an unconditional surrender, thus ending World War Two.

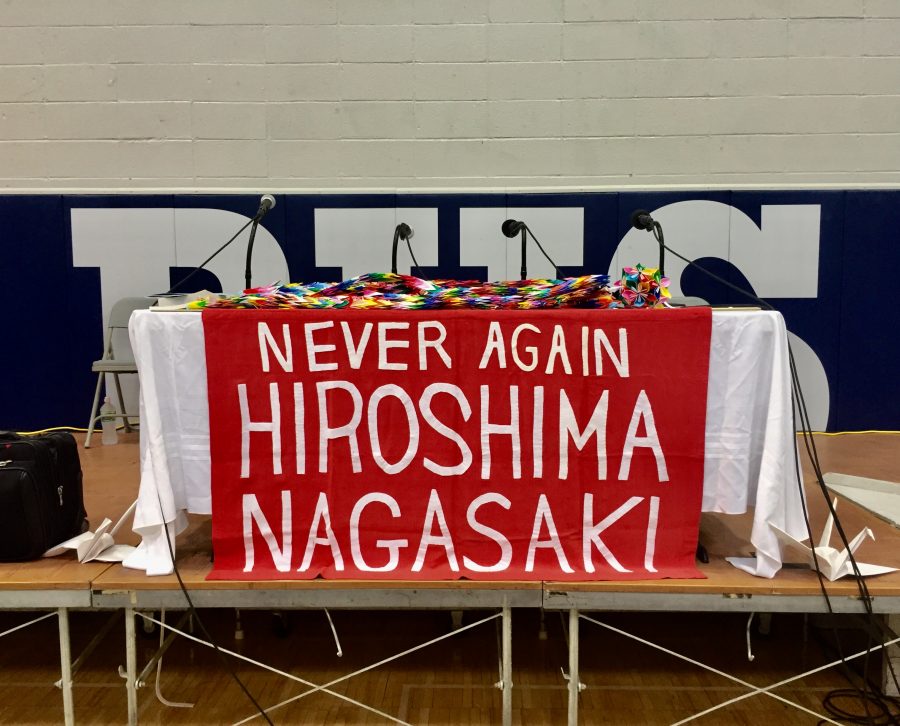

Sasamori is a survivor of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. She and Yasuaki Yamashita, a survivor from Nagasaki, gave testimony to the trauma they experienced seventy-three years ago at a school-wide assembly today at Burlington High School (BHS). Students sat rapt in horror and empathy as they listened to the survivors share their stories.

Sasamori and Yamashita were brought to BHS by Hibakusha Stories, an organization that seeks to inform the next generation about the real consequences of nuclear weapons. “Hibakusha” is the Japanese word for “atomic bomb survivors”. Hibakusha Stories has reached over 40,000 schools, and is a part of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN). ICAN was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2017.

“We have an obligation to share so people understand,” Yamashita said. “We don’t want anyone to suffer like we suffered.”

Yamashita told BHS that sharing his story was difficult at first. But now, it has become integral to his healing process.

“This is my therapy,” Yamashita said, gesturing to the gymnasium full of students who sat at the edge of their seats, tears forming in many of their eyes.

“I had a hard time wrapping my mind around [the stories],” sophomore Lila Iyengar Lehman said. “Then I just felt really sad.”

Both Yamashita and Sasamori gave graphic details about the day they saw their cities burn.

“I saw people lying on the ground, people floating in the river, ” Sasamori said.

She described the landscape as a “fire ocean” and compared the thousands of the dead and dying to rows of drying fish in a fish market. It was in these rows that her mother, five days later, found Sasamori, who suffered from severe burns on her upper body and face.

“[The stories] put a new perspective on how we view that point in history,” sophomore Lucy Kraus-Cuddy said. “It’s important to hear these stories and make sure they are remembered.”

Both Yamashita and Sasamori shared their gratitude for the students. At one point Sasamori invited the audience to smile. She gazed out at the young faces before her as their somber expressions softened into smiles.

“Your energy makes world peace,” she said.

When the students were dismissed from the assembly, dozens stayed back to personally thank Yamashita and Sasamori for sharing their stories, and give them a hug.

“Watching someone be vulnerable enough to go up there and speak inspires you to go up and do it as well,” freshman Shamura Awayle said.

While the students connected with the humanity and courage of the guests, there is a deeper purpose to sharing their stories.

John Reuwer, MD, an advocate with Physicians for Social Responsibility (PSR), is working with Hibakusha Stories to educate others about the effects of nuclear weaponry.

“These testimonies are very powerful,” Reuwer said. “[They] help your generation understand that if these weapons are used, it’s a horrible thing we can’t deal with.”

PSR is one of the supporters of Hibakusha Stories, and a major advocate for the global abolition of nuclear weaponry, along the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF). The Vermont branch WILPF wrote the grant that brought Hibakusha Stories to Chittenden County. Representatives from both organizations were present at BHS today to advocate for nuclear disarmament.

A global nuclear weapon ban was passed by the United Nations in 2017, but 50 countries still need to ratify that treaty. The United States is one of these countries.

“We fell asleep, and now the people in power have forgotten,” Reuwer said.

The assembly BHS experienced today served to awaken a new generation, and encourage them to remember what happened in 1945.

“We need your help. Convince your country,” Yamashita pleaded. “One voice is not enough. Two voices are stronger than one. Our time is ending. You have enough time. Say, ‘no more weapons.’”

Photo: Halle Newman