Haunting Stories From Vermont’s Most Infamous Graves

October 30, 2020

By Lea Mihok

Going to a high school nestled between a thatch of woods and a 148-year-old cemetery is an unusual experience. When school is in person, students eat lunch on the grass while gazing out at headstones, and when the scoreboard lights up at a home game it illuminates the graveyard just beyond the turf, separated from the living by a thin chain-link fence. However, Lakeview is just one of a slew of unusual Vermont cemeteries. Here are the stories of five of Vermont’s strangest burial sites each with their own haunting tale.

The Doctor’s Window

Photo: Lea Mihok/The Register

In the 1800s, before the invention of Band-Aides or Penicillin, the world was a terrifying place. Possibly even more so than it is now. Supporting this theory is the rise in popularity of “security coffins” during the 19th century. These were coffins built to prevent an occupant from being buried alive. The most well known of these mechanisms involved a cord attached to a bell for a prematurely interred victim to ring to alert passerby. Other designs ranged from flag riggings to escape hatches. One relatively rare option for ensuring actual death was a window. Most people had a slight aversion to the idea that others would be watching them decompose, but not everyone.

Dr. Timothy Clark Smith was born on June 14, 1821, in Monkton, Vermont. He received a bachelor’s degree from Middlebury College in 1842 and a medical degree from the University of the City of New York in 1855. Over the years, he worked a variety of jobs and even served as a staff surgeon in the Russian army. In 1861 he was appointed as Consul at Odessa, Russia by then-president Abraham Lincoln. Smith suffered from taphophobia, the fear of being buried alive. This was perhaps a result of Smith’s deep entrenchment in the medical world. Whatever the cause, the doctor wanted to be sure he had options, even in death.

Smith commissioned a special design for his grave: A six-foot-long concrete shaft would be installed in the earth above his body. It would lead from a window on his coffin, positioned just above his face, to another that allowed someone on the surface to look down on him. The plan was executed upon his death in 1893. Some reports say that a bell was placed in his hand in the event of an unnatural awakening.

Photo: Lea Mihok/The Register

Today, at his final resting place in the Evergreen Cemetery of New Haven, Vermont, amidst the first rows of solemn headstones, stands a wide mound of earth about four feet tall. On the top, sits a large slab of stone, and carefully inlaid in that, there lies a window. The view through the glass has long been obstructed from years of condensation, but that doesn’t stop the imagination from filling in the space below. Over time rumors have spread, stories of when one could look down and catch a sight of a doctor’s skull, legends about a strange bell in a nearby general store with a cord that runs underground. One that rings at odd hours as if someone at the other end of that cord is calling. These stories continue to fright and delight, and it seems that although Smith was not buried alive, he found a way to live on through his burial.

Evergreen Cemetery: Town Hill Rd, New Haven, VT 05472

The Melancholy Man

Photo: Lea Mihok/The Register

John P. Bowman was born in Clarendon, Vermont in 1816. At 15 he began work as a tanner, and he would go on to make a fortune through the ownership of several tanneries. Despite Bowman’s commercial successes, his personal life was plagued by a series of tragedies. His first daughter died in 1850 while still in her infancy. His second daughter, Ella passed in 1879 in her early 20’s and his wife, Jennie, passed less than a year later.

Bowman, however, was cursed with a long life. To prepare for death, he commissioned the creation of a massive mausoleum. The structure consisted of 20,000 bricks, 750 pounds of granite, and cost $75,000 worth of Bowman’s fortune. On the stairs of the monument, Bowman installed a life-size statue of himself, climbing the steps, hat off and key in hand, ready to join his family.

Photo: Lea Mihok/The Register

While he waited for death, Bowman had the coffins of his wife and daughters relocated to the mausoleum. He built a mansion across the street so he could have a clear view of the memorial to which he would retire. He spent the rest of his years alone in the house until his eventual death in 1891, 12 years after his wife passed.

Bowman’s story is a romantic one of both loss and loyalty. Today, his statue remains, eternally walking up the steps outside. Tourists come to gaze at his sad eyes and slip flowers into his key-clenching fist. According to legend, Bowman may never have found the peace he so desperately sought. Some say that Bowman’s statue stalks the cemetery at night, others that if you visit after dark, his eyes follow you everywhere you go. Bowman’s slouched statue, so resigned to grief, so welcoming of death, proves haunting.

Laurel Glen Cemetery: Shrewsbury, VT 05738

The Middlebury Mummy

Photo: Lea Mihok/The Register

The story of this particular grave does not start in Vermont. In fact, it starts 3,677 years before Vermont was even a state. It starts in ancient Egypt.

Senusret III ruled as Pharaoh from 1878-1839 BC. His reign would lead to a period of peace and prosperity for his kingdom, but seven years before he became Pharaoh, he had a son. The young Egyptian was named Amun-Her-Kepesh-Ef. He lived for only two years before his death and mummification.

Hundreds of years later, after Europeans found their way to Egypt, many artifacts were stolen from the country and brought back to Europe. In the following years, this trend grew in popularity. The loot ranged from pottery and paintings to human remains, and it became difficult to distinguish between archaeologists and grave robbers. It is suspected that it was one of the latter who brought the mummy of young Amun-Her-Kepesh-Ef to Europe. There, the remains were said to have moved from auction to auction, finally landing in the hands of one Henry Sheldon.

Sheldon, the youngest of four brothers, was born in Salisbury Vermont in 1821. He grew up on his family farm and moved to Middlebury in 1841. There, he dabbled in an array of professions, from mail agent to real estate investor. In his fifties, he developed a passion for overseas oddities. In the late 19th century he purchased the mummified corpse of Amun-Her-Kepesh-Ef.

Needless to say, the quality of the shipping was not exactly “prime”. In a disturbing turn of events, the corpse was so damaged en route that upon arrival Sheldon refused to display it in his museum. He elected instead to store the mummified toddler’s body in his attic.

Sheldon died in 1907. The body of Amun-Her-Kepesh-Ef remained in the attic until 1945, when George Mead, a trustee of the Sheldon Museum, decided the mummy deserved a more respectful resting place. Upon his request, the remains were cremated and interred in his family plot at Middlebury’s West cemetery.

Photo: Lea Mihok/The Register

The grave is still there today. It lies on the left side of the cemetery, about halfway up. Like many of the older graves it is a simple rectangle, thin, grey, and slightly eroded. Engraved in the headstone are the Egyptian symbols for ankh and ba, representing life and soul. It stands about hip height, beside the grave of Caroline W. Hawley, Mead’s first wife. Behind that lies Mead and his second wife, Minnie Nourse Mead. The inclusion of the grave in Mead’s family plot is almost heartwarming. However, the gesture is wrought particularly hollow by the large cross carved in the place between the two Egyptian symbols.

Gazing upon the grave of the ancient toddler and remembering the utter disrespect imposed upon his afterlife, brings to mind stories of the infamous mummy’s curse. In those stories, strange accidents befall the people who trespass and loot the pyramids. The story of Amun-Her-Kepesh-Ef is enough to make one wonder if those responsible ever got their comeuppance.

West Cemetery: Middlebury, VT 05753

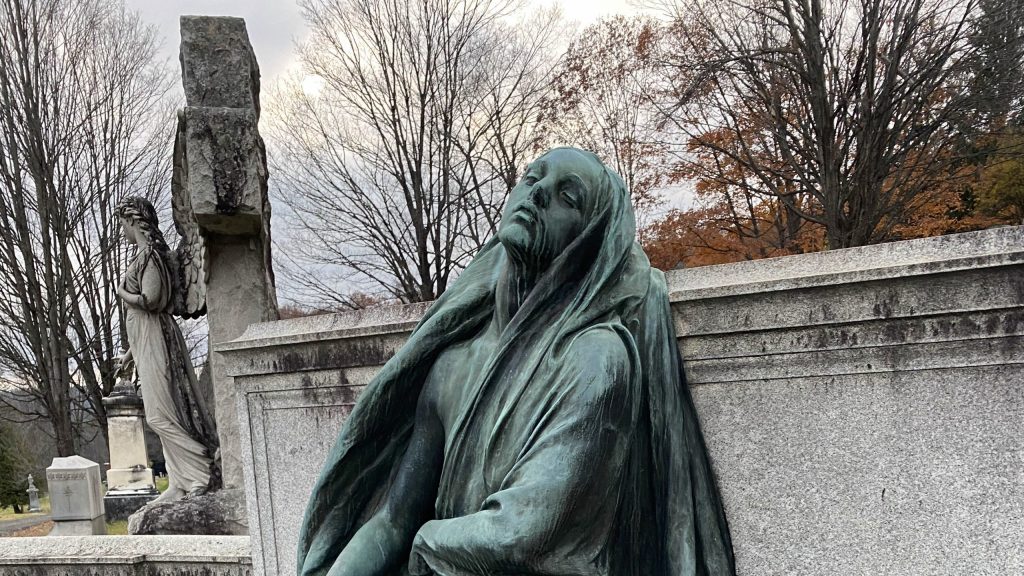

The Cursed Statue

Photo: Lea Mihok/The Register

The final resting place of Vermont’s John E. Hubbard, the namesake for Montepeliar’s Hubbard park, is an elaborate stone monument. The centerpiece of the burial site is a life-size statue of a melancholy figure wrapped in a shroud of bronze. The statue, nicknamed ‘Black Agnes’ is said to be cursed and has allegedly claimed the life of more than one Vermonter!

Legend has it, anyone who sits on Agnes’ lap will soon meet a disturbing end. One particularly well-known tale involves three Montpelier teens who snuck out to the cemetery late at night. Each one took a turn in the statue’s embrace. They waited until midnight, but there was no trace of supernatural activity. So, as the sun began to rise they made their way home, emboldened by a perceived triumph. However, in the following days, a series of mysterious accidents befell them. One teen was hit by a car, another fell down a flight of stairs and broke their leg, and the last drowned in a canoe accident. This tale is one of many, and despite the vagueness of details in each account, the legend of the cursed Agnes prevails.

Photo: Lea Mihok/Register

The cause of this curse is attributed to the man the statue was made for, John E Hubbard. Hubbard was born in Montpelier, Vermont in 1847 to an extremely well-to-do family. He had, by all accounts, a perfectly blissful upbringing, but during his lifetime Hubbard would become one of the most hated men in all of Vermont.

John Hubbard’s troubles began in 1890 with the death of Fanny Kellog, Hubbards aunt. At the time of her death, Kellog was in possession of a considerable fortune. In her will, she left much of her money to the city of Montpelier. John Hubbard, her only surviving relative, swiftly objected. There was a trial, and it was decided that the money would go to Hubbard on the condition that he use some of it to erect and maintain a public library. Hubbard did so, but this did not save him from the vitriol of the people of Montpelier, who felt he had stolen their payday away from them in an act of unforgivable greed. Hubbard was shunned for the rest of his short life. Nine years later he died and although he left the city most of his fortune, he was not forgiven.

Some say that it was this alienation that brought a curse to his grave; that Hubbard exacts his revenge against those who disrespect him in death as they had in life. Others attribute it to the greed of Hubbard himself. Whatever the cause, the legend of Black Agnes prevails.

Green Mount Cemetery: 250 State St, Montpelier, VT 05602

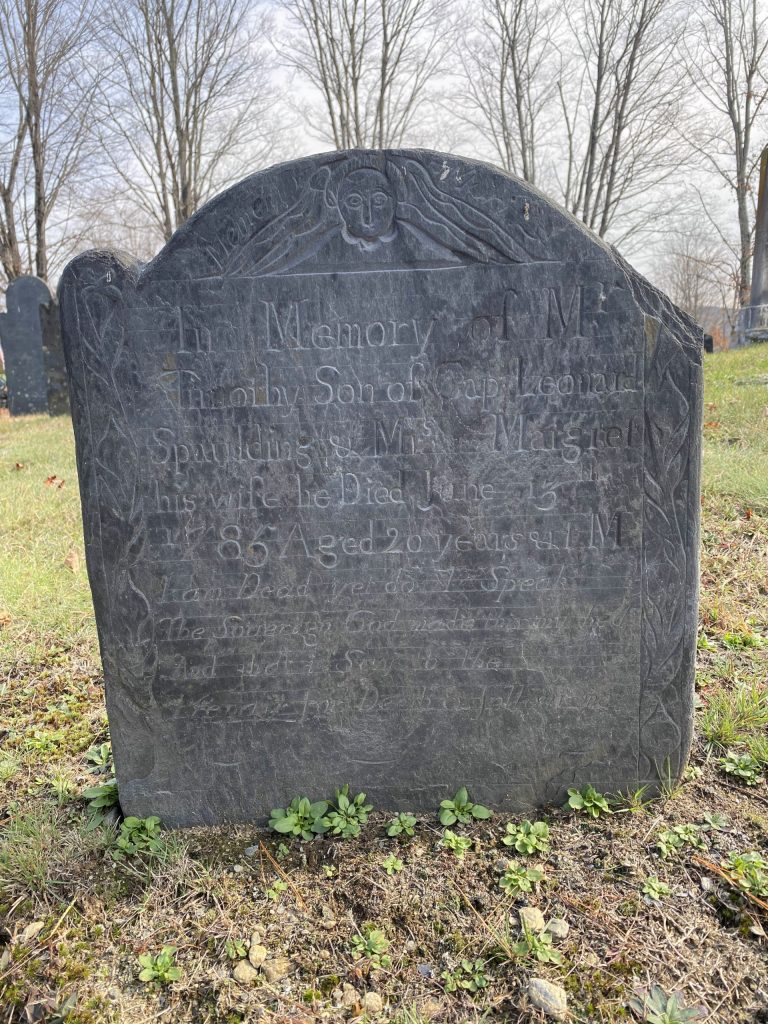

The Deadly Vine

Vermont has its fair share of underground mysteries, from the network of smuggling tunnels under Burlington to whether or not Ethan Allen really lies beneath his memorial. One of the most intriguing of these mysteries is the story of the Spaulding family and the deadly subterranean vine that tormented them.

Photo: Lea Mihok/The Register

Lieutenant Leonard Spaulding was born in 1728 in Westford, Massachusetts. After his service in the French and Indian War and the American Revolution, he became known locally as something of a hero. Eventually, he and his wife settled in Dummerston, Vermont. Together, they had eleven children, but fertility may have come at a cost: a curse.

Photo: Lea Mihok

In the 1780s the Spauldings began to die rapidly of consumption. The Spauldings, most of whom were in exceptional health, surrendered to illness surprisingly rapidly. By 1794, it had claimed the lives of seven of the Spaulding children, as well as that of Leonard himself. Such a score of sudden deaths was unusual and the remaining Spauldings began to suspect a curse. When another daughter fell ill, the family grew desperate.

In an attempt to end the curse, the Spauldings unearthed the most recently buried coffin and with it, they discovered a vine. It had grown from one side of the Spauldings plot to another, twisting from each coffin to the next. No coffin was untouched, and the Spauldings declared this vine the source of their curse. They suspected that every time it grew to reach another coffin a new Spaulding would fall ill. As a last resort, they destroyed the vine and had the corpse of the most recently interred Spaulding burned. Miraculously, the afflicted daughter soon recovered from her illness and became the last Spaulding to be affected.

Now, one can still find the row of six small, dark, graves where the vine once made its way in the Dummerston Center Cemetery. They are unassuming, but looking more closely one will find heart-rending inscriptions dedicated to too many lives cut short at once and know that whether or not it was the vine, the Spauldings were cursed.

Dummerston Center Cemetery: 914 East-West Rd, East Dummerston, VT 05346

Photo: Lea Mihok/The Register

Works Cited:

Abramovich, Chad. “Cemetery Safaris and Green Mountain Memento Mori.” Obscure Vermont, Obscure Vermont, 2016, urbanpostmortem.wordpress.com/2016/04/27/cemetery-safaris-and-green-mountain-memento-mori/.

“Black Agnes Statue.” Vermont History, Vermont Historical Society, vermonthistory.org/black-agnes-statue.

Burns, Meg. “Henry Sheldon and His Museum.” Henry Sheldon Museum of Vermont History, Henry Sheldon Museum of Vermont History, www.henrysheldonmuseum.org/henry.

Cherrell, Kate. “Timothy Clark Smith: The Grave With a Window.” Burials & Beyond, Burials & Beyond, 25 Aug. 2019, burialsandbeyond.com/2019/08/25/timothy-clark-smith-the-grave-with-a-window/.

“Discover the Remarkable Story of a Mummy Buried in Vermont!” The Vermonter, The Vermonter, vermonter.com/middlebury-mummy/.

“Dr Timothy Clark Smith (1821-1893) – Find A Grave…” Find A Grave, Findagrave.com, www.findagrave.com/memorial/19739131/timothy-clark-smith.

“Dummerston Vine.” Atlas Obscura, Atlas Obscura, 28 May 2012, www.atlasobscura.com/places/dummerston-vine.

“Dummerston.” Dummerston, Windham Co. VT, Rootsweb, sites.rootsweb.com/~vtwindha/vhg5/dummerston.htm.

H, Jim. “Story Behind the Ancient Egyptian Prince in Vermont.” Historic Mysteries, Amazon, 24 Oct. 2020, www.historicmysteries.com/mummy-in-vermont/.

Hoare, Nell Darby and James. “Victorian Egyptomania: How a 19th Century Fetish for Pharaohs Turned Seriously Spooky.” All About History, www.historyanswers.co.uk/people-politics/victorian-egyptomania-how-a-19th-century-fetish-for-pharaohs-turned-seriously-spooky/.

“John Porter Bowman (1816-1891) – Find A Grave…” Find a Grave, Findagrave.com, www.findagrave.com/memorial/3567/john-porter-bowman.

Kimmel, Jamie. “Haunted Vermont: The State’s Scariest Sites.” GoNOMAD Travel, GoNomad, 22 Oct. 2019, www.gonomad.com/5646-haunted-vermont.

Levitt, Alice. “Death Becomes Them.” Sevendays.com, Seven Days, 29 Oct. 2008, www.sevendaysvtA.com/vermont/death-becomes-them/Content?oid=2135544.“Lieut Leonard Spaulding Sr. (1728-1788) – Find A…” Find a Grave, Findagrave.com, www.findagrave.com/memorial/57770374/leonard-spaulding.

![Check out Rose Howell's article "Teaching Conflict": https://bhsregister.com/9661/news/teaching-conflict/

“I know that some people have colleagues who disagree with me because they don’t think these conversations should happen in school, [but] where else should they happen then?” ~Social Studies teacher Francesca Dupuis](https://scontent-ord5-1.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.29350-15/404979361_1569222083889381_8162261023681050366_n.jpg?_nc_cat=101&ccb=1-7&_nc_sid=18de74&_nc_ohc=RHOhiTkucIgAX9i9OIz&_nc_ht=scontent-ord5-1.cdninstagram.com&edm=ANo9K5cEAAAA&oh=00_AfDvefW7hOPJEWQXiafhqZSFlGqW7IQC9rpAVV3pFKgt8w&oe=65B50250)

Olivia Little • Jun 13, 2022 at 1:02 pm

I have never seen a grave like this before. This is the first time I’ve seen one like this.

dave ide • May 1, 2022 at 5:52 pm

Craftsbury Common. I am VERY familiar with that cemetery. My dorm at Sterling College was directly across the street (I was a student there from 1987-1990). Let me sum up what I and other students saw. Balls of light dancing in the far left corner of the cemetery on a nightly basis….mostly orange. It was so common that it was normal to us to see. We tried to debunk it, but there is no way possible that it was someone joking with a flashlight. We even slept out in the cemetery on warm nights. This was three dimensional that was in front of graves, then zoom up into the air about 20 feet, then back down to another grave, then back to the corner of the cemetery where there was a massive 10 foot tall hedge of old thorn bushes mixed with multiflora rose. No way in hell could any person walk thru that. We couldn’t figure it out, but we weren’t scared of it. Any way, my name is David Ide and that was just one of many paranormal experiences that happened up there.