From heart transplants to Google Meets: the complicated ways BHS faculty are coming to terms with the school closure

October 20, 2020

On September 16, Chris Sharp, a Burlington High School (BHS) art teacher of 29 years, opened his all-faculty meeting invitation and clicked on the Zoom link. He and his colleagues got an announcement they were not expecting: because of test results indicating elevated levels of Polychlorinated Biphenyls, or PCBs, in the building, BHS would close immediately to in-person learning for the semester. In a grid of dozens of pixelated, muted, rectangles, Sharp saw his colleagues’ faces transform in astonishment and disbelief as they tried to comprehend what they were hearing.

As part of the ReEnvisioning Project, contractors tested air and soil for hazardous materials this summer and detected PCBs in the 1964 building. PCBs are often found in lighting fixtures and caulking of buildings built between 1929 and 1979, when the EPA banned their use. PCBs have been proven to cause a multitude of serious adverse health effects.

“I was shocked that the school was closing down,” Sharp said. “I thought the buildings’ impending rebuild was the acknowledged solution to updating all the outdated and unhealthy materials that were used as best practices from a less informed time.”

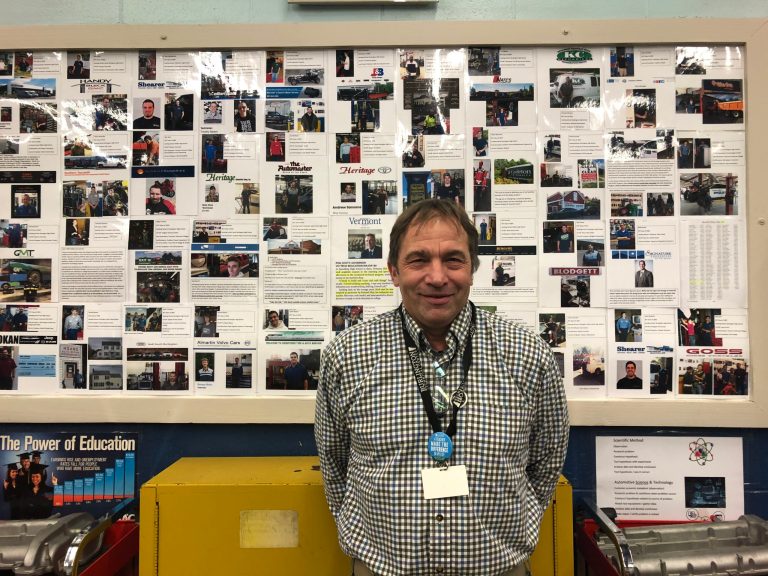

Bob Church is the automotive instructor at Burlington Technical Center (BTC) and has been teaching in his F building classroom since 1990. Those who walk into the room are greeted by dozens of then and now photos and write-ups of his past students lining the walls. This is Church’s passion project. His shop is like a second home.

Photo: Register

“I’m still kind of in disbelief,” Church said. “I spent all summer [in the classroom]. I put a new lift in. The shop looks the best I ever had in my 30 years and it’s so frustrating to me in a way, I don’t know, I’ve got so much of my life in that place.”

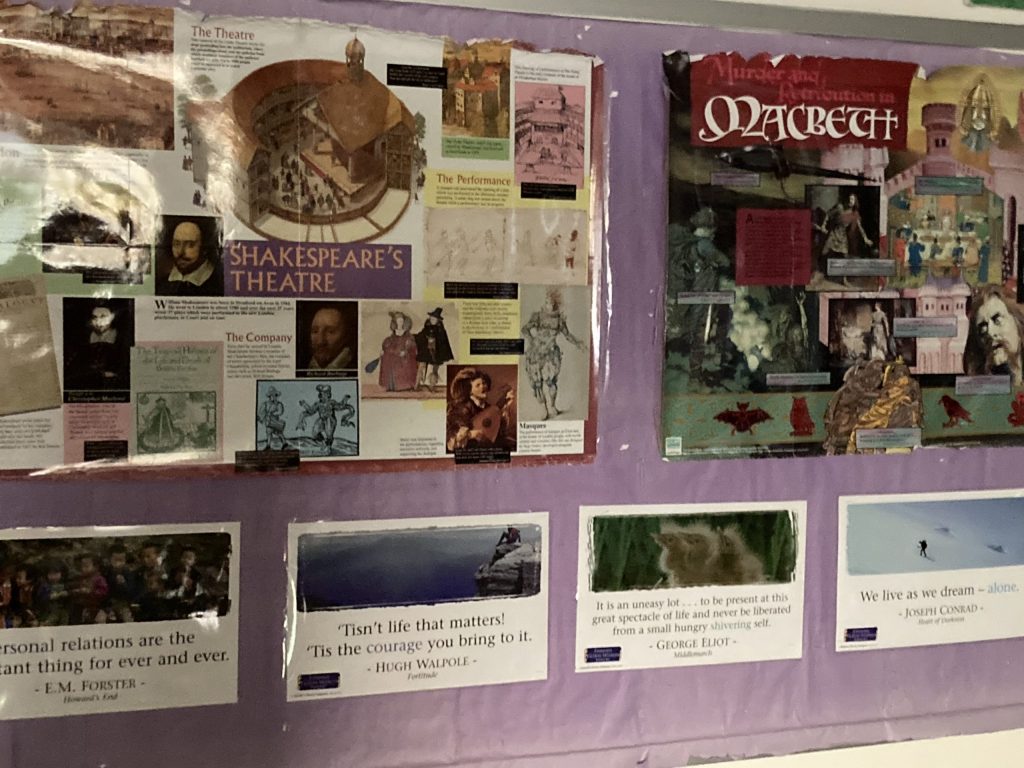

Tammie Ledoux, who is in her 21st year teaching English at BHS feels a similar disappointment. Per Ledoux, she had finally overcome her anxiety about COVID-19 and skepticism regarding school reopening. For her, putting her Macbeth posters up embodied an acceptance and excitement towards school beginning.

“The day that I left the school after putting all those posters up was when I got the phone call and it was just like I had just gotten my cynical brain wrapped around the fact that everything was going to be ok…and the day after that we were closed, so it was pretty heartbreaking.”

Photo: courtesy Tammie Ledoux

Church’s classroom had PCB levels of 1900 ng/m3. PCB levels for Ledoux’s classroom were not included in the sampling results. However, PCB levels in C building, where Ledoux teaches, were much lower, the highest measuring 130 ng/m3.

The Vermont Department of Health recommends that PCB levels in school air be below 15 nanograms per cubic meter, far more conservative than the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) 500ng/m3 standard.

Results from the testing at BHS found the highest levels of PCBs in F building where BTC and several other BHS classrooms are located. Seven out of the nine rooms tested in F building exceeded the EPA standards; one room measuring as high as 6300 ng/m3. Not a single classroom in the five other BHS buildings included on the test sampling results exceeded 300 ng/m3.

Ledoux has abandoned the posters and Church has been shut out of his shop. Now they, like most other classroom teachers, face the challenge of teaching online.

“When we do distance stuff with technology you spend all this time staring at a screen and your worldview and your optimism becomes very limited,” Ledoux said. “When you lose those actual physical connections with folks it’s easier to become more paranoid and more cynical and more isolated.”

Church is currently teaching his automotive class entirely online while looking for alternative spaces for him and other BTC teachers to teach in-person. In the meantime, he is doing everything he can to stay connected with his students.

“I’ve made a couple home visits for students that kind of dropped off my radar,” Church said.

While most classroom teachers are teaching virtually from their homes, the BHS custodians do not have that option. Chris Charbonneau was the Head Custodian at BHS. He had been at BHS for the past 12 years and in the district for a full 27. All of the BHS custodians were split up and dispersed to various other schools in the district when BHS closed. When I spoke with Charbonneau, on September 28, it was his first day at Edmunds Middle School (EMS).

“The [relocation to EMS] just happened because of the PCBs,” Charbonneau said. “It’s kind of devastated every one of my coworkers. No one knows where they are or are going to be.”

Charbonneau, self-identified as someone who “doesn’t like change that much”, finds the uncertainty of the situation and being separated from his coworkers difficult.

“When you are used to coming in every night to a routine and stuff, and it’s just, you don’t know where you’re going and you don’t know how long you’re going to be [there].”

Following the announcement that BHS was closing, Charbonneau applied for the head custodian position at Hunt Middle School. Charbonneau has since gotten the job, and will not return to BHS.

David Burbo is a locksmith and low voltage technician who has been in the Burlington School District for 43 years. When I asked him a question referencing the reopening of the building in January, both he and Charbonneau laughed to themselves.

Photo: Nora Jacobsen, Register

“I figured they’d close [BHS] down for a little while, maybe get it cleaned up and get right back at it, but with the Covid stuff now and the PCBs they are thinking about January opening back up,” Burbo said. “But I don’t foresee it, what they need to do is tear it down and start over.”

Burbo, like others who have worked in the buildings as long as he, has long been aware of many contaminants within BHS, including PCBs. Many faculty members have had air quality concerns beforehand, and question the existence of a pattern.

“I used to do electrical and I used to take out the ballast and they were full of PCBs so we just had to get rid of them, box them up and ship them out,” Burbo said. “Where they went, I have no clue but other than that, I didn’t realize [BHS] would close up the way it did.”

Air quality concerns within the building date back to the 1990s. In 2002, air quality testing was performed after five people associated with BHS contracted potentially life-threatening heart conditions. Following the testing, district officials reported no air-quality problems or linkage between the illnesses and the building. Following the health concerns, work was done on the building’s ventilation system.

Laura Allyn, a health and family and consumer sciences teacher, has taught at BHS for 25 years. In 2002, she suffered congestive heart failure brought on by a viral infection, which she reports being connected to the building’s air circulation.

“In the fall of 2002 I got really sick and our union leadership realized at that point that there were more of us…all with heart-related ailments,” Allyn said. “Mine ended up being the worst because I was only 40, I was healthy, I was busy, it never even occurred to me that I could have that kind of heart damage.”

Allyn ultimately had to be treated in Boston and received a heart transplant.

“A heart transplant is not a cure, it’s a treatment and that’s the truth,” Allyn said, referencing her recovery. “Basically, you get the heart transplant but it took probably ten months to adapt to the side effects of the medications so that I could even go back to work part-time. And since then it has been almost like a part-time job to keep the medications even, to keep my health even, to stay healthy, to stay well, to be able to still work.”

Four years later, air quality concerns arose again when several E building teachers developed strange rashes that worsened while in the building and got better while out of the building for extended periods of time. In November 2007, an outside consultant was hired by the district to test the building’s levels of carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, mold, airborne fungi, and other possible irritants. Once again, no direct connections between the health concerns and the building were found.

I spoke to one of the teachers who had health problems and received treatment back in 2008. This teacher chose to keep their identity confidential over the fear of “being a lone person just standing up against the school district that [they] work for”.

“The biggest difference [between 2020 and 2008] is the fact that [the air quality] is already being dealt with as something serious,” the source said. “People at the district level and above are taking it seriously versus when we had it happen [in the past].”

Allyn is also relieved that air quality concerns are being taken seriously, this time around.

“I like the fact that our school board is working with our state department and finally taking this seriously,” Allyn said. “Because I do know that in 2008 when there was another round of air-quality trouble and there were people who suffered from rashes and all kinds of trouble with that…it was kind of just brushed under the rug.”

The recent testing showing elevated levels of PCBs affirms these longstanding concerns. This anonymous teacher wants answers. Specifically, the results of the previous tests to know what they tested for, whether they tested for PCBs, and if not, why?

“I’ve actively been calling our local union and they have told me they have requested the data from the district,” the source said. “I have also been in contact with the VT-NEA (Vermont-National Education Association) and seeking the advice of some other experts on PCBs.”

This skepticism about how air-quality has been dealt with in the past seems to be present across the board.

Church spoke at length about his gratitude and appreciation towards all the public servants and at no point assigned blame. Still, he cannot help but question the parallels to air quality issues in the past.

“We’ve had former staff leave with various health issues, and I’m not saying the building environment contributed to it, but when you read the data on the PCBs and stuff, you do have to wonder if the environment did contribute to some illnesses within staff,” Church said.

Teachers are working to come to terms with this new reality.

“The current school board or administration is not at fault nor are they negligent,” Sharp said. “…There are no villains, only the challenge of a problem that needs to be corrected, and more importantly, the opportunity for Burlington to design and build a new vision of education.”

Church expressed a similar attitude.

“I think we could spend a lot of time trying to find blame and for me it would be wasted energy when we should really just try to move forward,” Church said. “…My hope is everybody focus on the goal of the kids and what’s in the best interest of our kids in the short-term and in the long-term.”

When asked about what she wished people knew, Allyn spoke to her students.

“Probably a quarter [of my students], maybe a little less, are really struggling with [the school closure],” Allyn said. “I would like them to know that their teachers are here for them, and I understand it, and a lot of teachers are struggling, too.”

Anyier Manyok • Feb 7, 2021 at 3:36 pm

Thank you so much, this was great!

Jackson Haugh • Oct 21, 2020 at 2:57 pm

This was great!