The BHS One-Acts were back after a one-year hiatus, and this year’s program was filled with as much hilarity and emotional punch as ever. What makes the One-Acts special isn’t just their short duration, it’s that they’re traditionally almost entirely student-run and often written by students. The One-Acts give students a chance to flex their creative muscles and be leaders in a way most of them have never experienced. The plays range from ten to 30 minutes, and from three to eight actors. With five plays in total, the evening had something for everyone.

Every Novel You Read In High School (In 25 Minutes or Less)

The program began with “Every Novel You Read In High School (In 25 Minutes or Less)” by Ian McWethy, directed by Drama Department Head Peter Bowley. The play stars a struggling troupe of actors who have been hired by a school principal. Their task is to summarize his students’ summer reading for them, in hopes that they don’t fail their standardized tests. Highlights of this One-Act included “The Scarlet Letter” as a *cough* Disney *cough* musical, with songs sung half-heartedly acapella as the troupe rushes to cover the whole plot in three minutes. As the one acts are known for being primarily student-led, starting the program with a play that was neither written nor directed by a student was a bit odd, but to get the audience warmed up, it was a good choice. The witty script and lively cast drew laughs.

Waiting For the End of the World

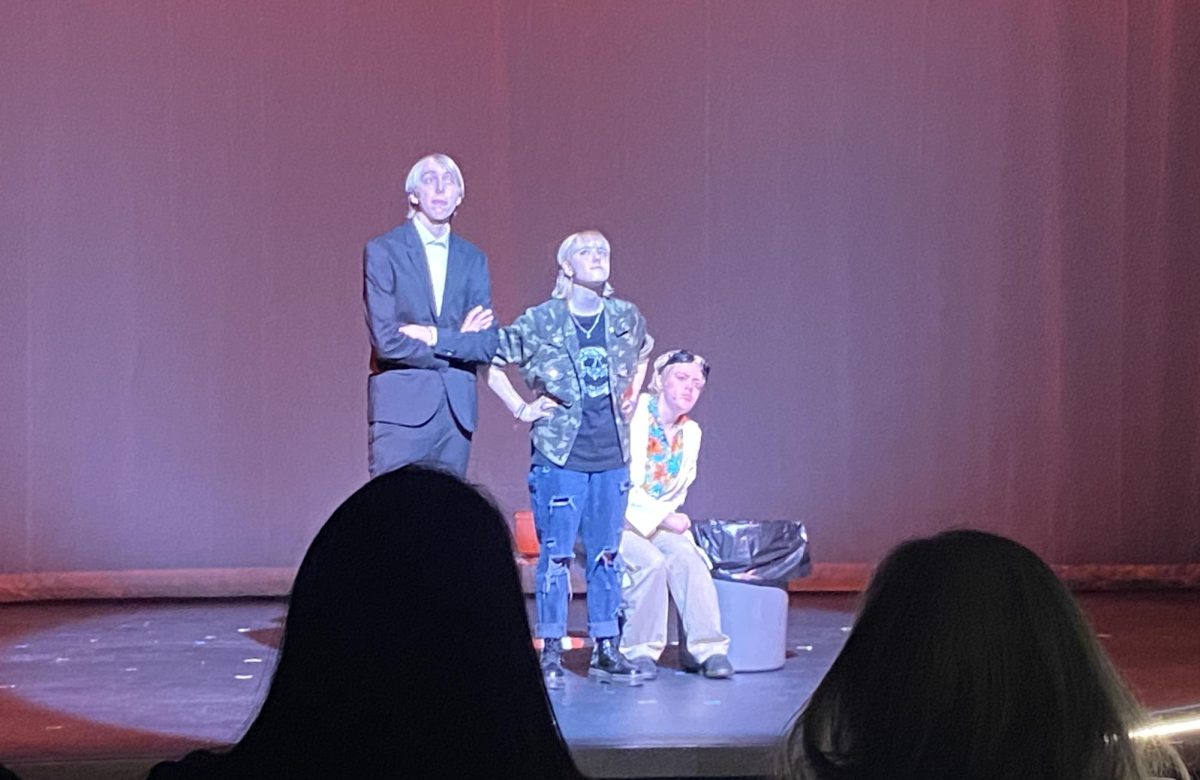

The comedy did not end with the first play. Next up was “Waiting For the End of the World” by John Shanahan and directed by Nora Perry ‘24. It centers three out of four Horsemen of the Apocalypse ready for the end times but still waiting for number four: Famine. Can there be an apocalypse with only three Horsemen? How important is Famine, anyway?

Starring Kuba Thelemarck, Avery Eringis, and Luca Stanton, all of whom gave stand-out performances in the fall musical “The Lightning Thief,” this play was almost too perfectly cast. Eringis ‘26 played War as a tough girl in an army jacket, who surprisingly seemed to be the most laid back of the three. Thelemarck ‘26 played Death as a tired, no-nonsense and burnt out businessman who could not wait for the apocalypse to be over so he could take a break from work. Rounding out the cast, Stanton ‘26 played Pestilence as a flamboyant, troublemaking, mad scientist cooking up new afflictions in his lab. These subversions of the characterizations the Horsemen usually receive —a non-sadistic Death, a non-belligerent War and a non-sickly Pestilence— were interesting.

The cast played off each other very well. Outside of the singing and dancing of the musical, their acting and comedic chops were given a chance to shine. Perry’s directing served the script and the cast very well, playing to the strengths of each one. Apart from a slightly confusing final moment which could have used some more clarity in its direction, this play may have been the best and most polished of the night.

Cheaters

Next was “Cheaters,” written by Annie Harte ‘26 and directed by Bowley. This ten-minute play is about four students with very different personalities, all in detention à la Breakfast Club, for cheating on a personal essay about what makes them most unique. They are left in a room alone to discuss who among them deserves to fail the class. Each student opens up about their struggles and tries to find their own answer to the admittedly rather absurd essay prompt. Harte is clearly a budding talent when it comes to playwriting. She creates memorable characters and a compelling story for each of them. She also demonstrates her capability for comedic dialogue with a few witty lines.

One of the weaker points in the script, the character’s tendency to simply monologue their innermost thoughts rather than convey them through subtext, was exacerbated by directorial choices made by Bowley. When each character gave their monologue, they turned to the audience and had a spotlight on them, conveying to said audience that the character is talking to them, rather than to other characters. This made it jarring when other characters responded to the speaker. Occasionally, the other actors would still be unlit while saying their lines, which further confused things. Harte’s script could have been conveyed in a way that highlighted its better qualities, and Bowley may have missed the mark on this one. I hope Harte will continue to write, and that in the future her plays will get the direction they deserve.

Overheard Hell

After intermission came “Overheard Hell” by Amy Chung ‘23 and directed by Richie Amerson ‘25. Chung has written a play for the One-Acts before, notably “Shawty Doesn’t Have Apple Bottom Jeans She Has Blood on Her Hands” in 2021’s festival. “Overheard Hell” has a similar format to “Shawty”, featuring three scenes on the stage, with the action rotating between each one. Unlike “Shawty”, which is mainly set in a police station, “Overheard Hell” is set in a busy restaurant, with some odd pairs on dates at three tables and an overworked waitress running between them, struggling to keep up. The audience is even invited in on the action: the waitress talks to us as if we were her fourth table who has just been seated.

From our vantage point in the restaurant, we observe two young musicians on the worst first date ever, a middle aged couple on the verge of divorce, and two college students who are only there to steal the dinnerware. Tuition is expensive, after all. Joke after joke lands with the audience as we see each date devolve into disaster. The poor waitress becomes involved in every drama, including a physical altercation with one of the musicians as he attempts to serenade his date with a ukulele. Amerson’s directing supplemented the script with a few visual gags, and the cast’s comedic timing was great, with few exceptions.

However, the three-scene format does have its limitations as well as its strengths. At some points in the script, it seems as though time would freeze for one table while the others played out their scenes, but at other times it seemed like the play was running in real time and we were picking back up in the conversation at a later point than we had left off. Amerson chose to have the actors freeze during the other tables’ scenes, which was hilarious at points, especially when Shearer’s Musician was frozen in place, about to strum his ukulele, and DeMink’s Musician was simply looking on in horror. This decision could also have been made out of necessity to not distract from other scenes with unnecessary movement.

The script could have used a final clean-up, but was overall very funny, and had the audience nearly on the floor laughing.

The Final Rose

Closing out the night was “The Final Rose” by Bekah Brunstetter directed by Rowan Thayer ‘24. Based on “The Bachelor,” the story follows Jeremy, a young man about to choose who the final two contestants for his heart are. He feels a genuine connection with Beatrice, played by Emma Stearns ‘27, but despite urging him to “follow his heart,” the producer clearly wants him to pick Meredith, played by Lincoln Safran ‘25 or Rebecca, played by Nigina Azizova ‘25.

In their director’s speech, Thayer commented that they thought everyone would pick a comedy to direct, so they chose something they thought could make people cry in addition to making them laugh. The story of “The Final Rose” does become very emotional, especially in Beatrice’s post-elimination interview. Stearns does an excellent job with the character, going from hopeful and in love, to crushed and confused after she is eliminated.

The rest of the contestants are very funny. Azizova’s gothic, scary and standoffish Rebecca contrasts and plays off of Safran’s sweet southern belle Meredith. There is not much to either character, but Azizova and Safran make you genuinely root for the characters rather than write them off. Good actors can make even characters that appear to be one-note shine, and Azizova and Safran accomplish this throughout “The Final Rose.”

Thayer’s directing brings you into the story and keeps its momentum through different scenes. Transitions can kill a short play, but Thayer has them nearly seamless as we go from the set of the show, to a private conversation between Jeremy and Beatrice, to a romance between a camera operator and a production assistant. Thayer has admirably put together a production that, if it doesn’t make you outright cry, can certainly make you feel for its characters.