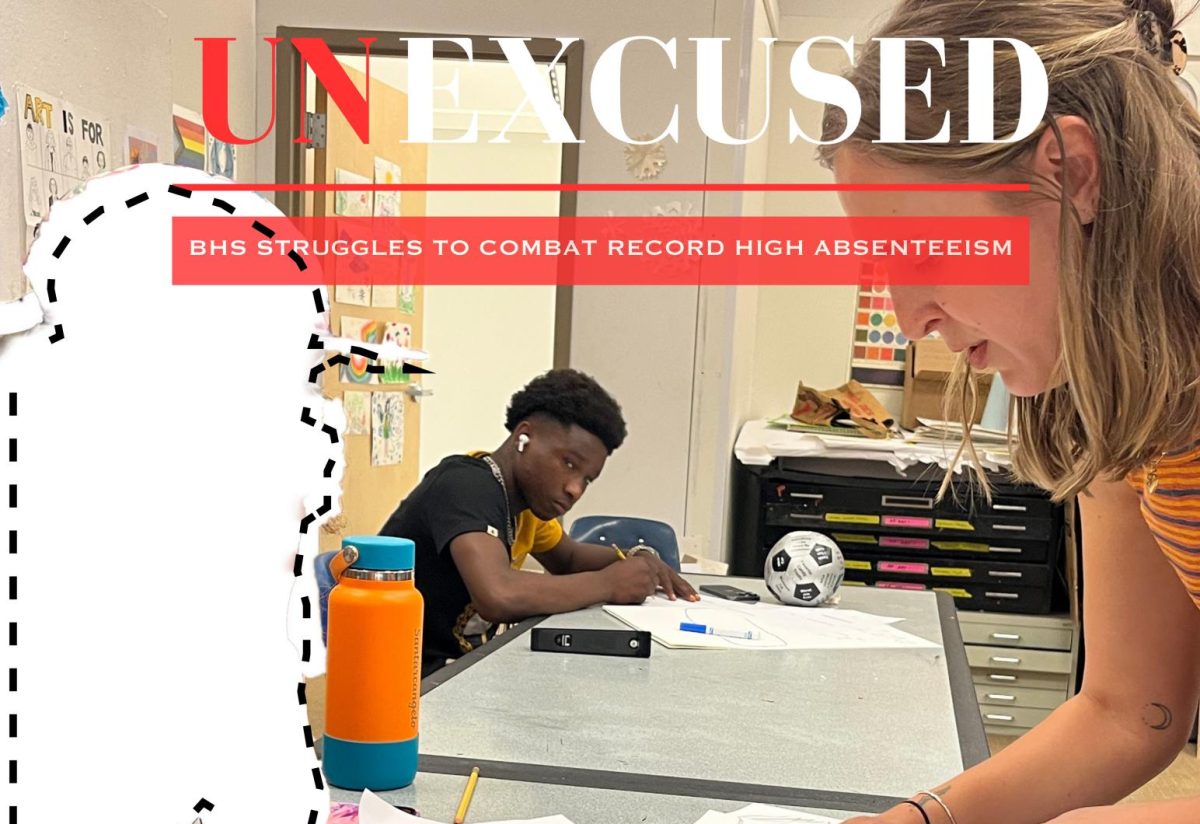

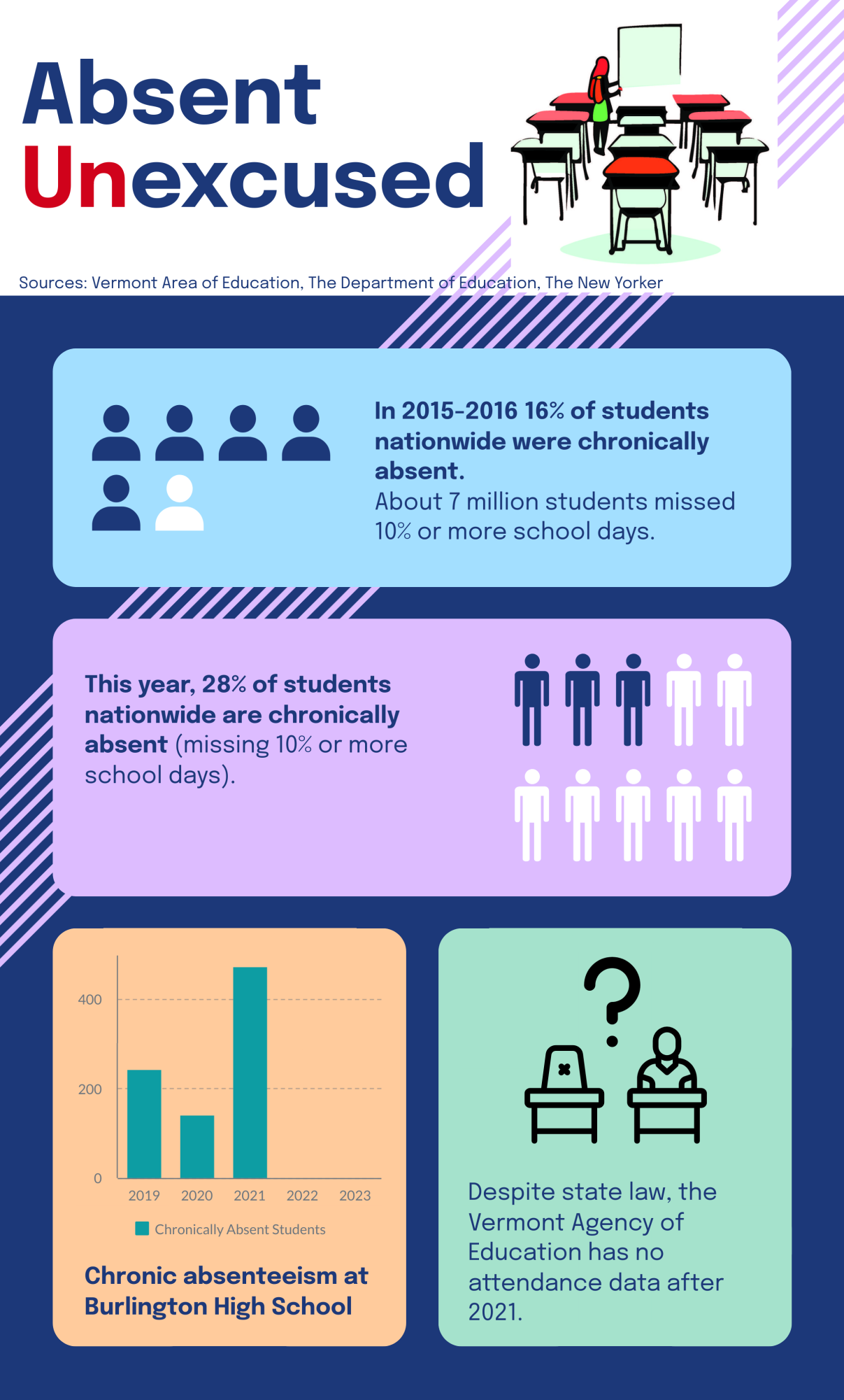

28% of BSD students were chronically absent last school year – having missed more than 10% of school days. This follows a nation-wide trend of increased absenteeism in recent years. The chronic absenteeism rate during the 2023 school year was 75% higher than it was in 2019 among states who report their attendance data to the Department of Education.

Social Studies teacher Korey Whitfield feels strongly about the problem.

“It’s a big issue that was surprising to me – having been a teacher in several different other schools before coming here. It’s something that is really quite different from all the other places that I’ve been,” Whitfield said.

Math teacher David Williams regularly struggles with absenteeism and tardiness in his classes. “I have a lot of students that consistently do not attend class. I have some students who are on my roster who I’ve never seen this entire year,” Williams said.

Absenteeism is associated with worse educational outcomes. Students who were chronically absent for at least one year, between grades 8-12, were found to be more than seven times more likely to drop out of high-school in a 2012 study of Utah public schools.

“You can look at the numbers,” Whitfield said. “There is a direct correlation between [being in school] and what your career path is and your ability to make money after high school. Being in school is an opportunity to improve your livelihood throughout your life.”

Absenteeism appears to be more prevalent among the underprivileged. The rate of chronic absenteeism among BSD students who qualified for free and reduced lunch was roughly 30% higher than the general population last year. Absenteeism affects Black and Hispanic high-school students at a higher rate as well, according to statistics from the Department of Education.

“I’m seeing that a lot of our students of the global majority, or students that are in a lower income bracket, are the ones that are more likely to have attendance issues,” Whitfield said. “So for me, that in and of itself is an equity issue.”

Molly Doran, who was originally hired to support student attendance, and now serves as the Dean of Students, cites the Covid-19 Pandemic as a reason BHS is experiencing attendance problems.

“[Absenteeism] definitely got worse [after the pandemic].” Doran said. “Our ninth graders – they were in fifth grade when COVID happened – and that’s a really formative year for social and educational development… [the pandemic] had an impact on all of those things. It impacted people’s competence and willingness to be in school.”

Williams shared a similar sentiment.

“I would say post COVID [the attendance issue] has gotten worse. Whether it’s tardiness or absenteeism. There’s a lot – more than I’ve seen before,” Williams said.

Vermont has laws in place to regulate the issue of absenteeism. If a student enrolled in a Vermont public high school fails to attend, a truant officer appointed by the district will investigate the student’s situation. If the truant officer finds the student absent without cause, they will notify the person “in control of the student.” If the student continues to fail to attend school, this person “in control of the student” will be fined and prosecuted by the State Attorney.

However, despite what is mandated by law, the most recent record about truancy in Vermont on the Agency of Education website is from February of 2022, nearly two years ago, and it asks for an extension because data collection is difficult to do during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“It seems like after COVID, [truancy court] is not really happening,” Doran said.

Now workers from the Department of Children and Families visit families with chronically absent students. However, prosecution is avoided.

“It’s less of a punitive approach and more of a supportive approach,” Doran said. “[But] I think [students] are also seeing that there are not really many consequences if they’re not coming to school, in terms of no more truancy court.”

At the beginning of the school year, BHS introduced a new disciplinary policy which sought to decrease absenteeism. After receiving five absences in a school week, students would receive an after-school detention. Five cumulative tardies would result in the same consequence. If this occurred two weeks in a row, a parent conference would be scheduled. If students skipped detention, they would receive an in-school suspension. However, this policy proved difficult to enforce.

“When [it] was originally created I don’t think that the principal realized the scope of our attendance challenges,” Doran said. “So it wasn’t really realistic to bring parents in for every student that’s not attending class. We had so many unexcused absences that tardies weren’t even part of our detention policy because the number [of absences] was so high.”

The detention policy was suspended so that the administration could evaluate its effectiveness.

“We found that a lot of students who were assigned to detention and went, made no change to their day to day behavior,” Principal Sabrina Westdijk said. “They were going to detentions, but they were [still] cutting classes. So we decided [the policy] wasn’t effective at all.”

Teachers say that they are still looking for a consistent and enforceable policy from the school.

“One thing that surprised me [when I came here] is that there’s no attendance policy,” Whitfield said. “There’s no clear guidelines or accountability for students in terms of their attendance and I think as a result it’s an issue for many students.”

Nikolas Homan ‘25, feels similarly.

“It seems like many of my [classmates] regularly make the decision to not show up to class because they know that there will be no consequences for them,” Homan said.

Administrative turnover has been a roadblock in the way of the development and enforcement of attendance policies at BHS.

“[At the beginning of the year] we had new principals, assistant principals, a new Director of School Counseling, and then obviously, another principal change,” Doran said. “So that impacts our ability to change or enforce some of these policies.”

Currently, BHS is working on a policy of un-enrollment for students who rarely, if-ever, attend.

“Once a student is unenrolled, it’s easy to re-enroll them, but the goal is that they would have to come back and have a meeting with their counselor, administration, student support, or whoever, to figure out a plan of how we can get them back into school,” Doran explained.

The administration has also begun sending students who are chronically skipping classes – but still going to school – to meet with Dennis Clifford and BJ Robinson, members of the student support staff. There they receive academic support and build attendance improvement plans.

Westdijk believes that a holistic approach is required to solve the attendance issue, due to the apparent ineffectiveness of previous disciplinary policies.

“I think we’ve shifted away from looking at punitive consequences as being something that’s going to fix this and started to pay more attention to what is causing so many students to skip classes,” Westdijk said. “[Students are] here but are not going to some of their classes. What has to change, or what needs to be done, or what supports need to be offered to help them feel like they belong in those classes, and they can be successful in those classes? We can’t punish our way out of this.”