Marzie Schulman ‘27 is Jewish, has visited Israel many times and has family in the Israel Defense Forces. Schulman says she wishes there was more time devoted to the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict in class because so many students are not educated on it. In fact, the only time a teacher has discussed the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict was in her Civics class where they watch two-minute “CBS Eye Openers” videos.

Norah Miller ‘24 says that most of her teachers have not addressed the conflict at all, and those who do, address it quickly and then move on.

“I think the first time it was mentioned was a really quick connection to what we’re learning about in class, and then immediately, it was framed as ‘let’s not get into that though, because it’s too controversial’,” Miller said.

Like Schulman, Miller believes the conflict should be covered in class.

“I think talking about it would be academically, morally, philosophically really beneficial to people,” Miller said.

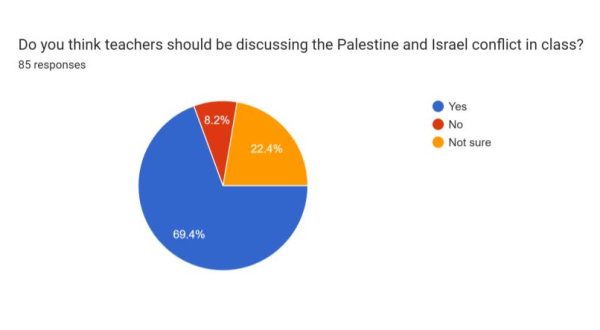

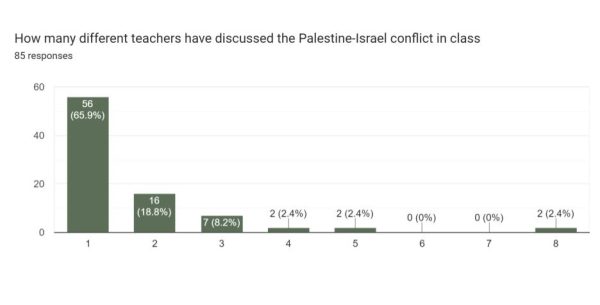

Schulman and Miller are not alone. In a survey of 85 students conducted by the Register, 69% believed that teachers should be discussing the conflict in class, while over 85% reported it had been brought up by either just one or no teachers.

“I would never have found out about it if not for my friends,” Barwaaqo Sugow ‘26 said.

Sugow is deeply invested in the conflict as well, and said her classes have not covered it, which is a problem because it is such a controversial and prominent source of grief in many people’s minds right now.

“I feel like, if the school just gave a time to talk about it, people would know about what’s happening,” Sugow said. “Then, if they were just to be dropped in a discussion about the conflict, they wouldn’t feel lost and they wouldn’t be quiet.”

Francesca Dupuis recently facilitated a discussion about the conflict in her 10th grade World History class. When Dupuis asked if students would be interested in having this conversation, 22 of 23 students said ‘yes’.

“I know that some people have colleagues who disagree with me because they don’t think these conversations should happen in school, [but] where else should they happen then?” Dupuis said. “I get it because you’re just protecting yourself, but sometimes that just fuels the ignorance and lack of understanding for other perspectives.”

Dupuis and a few other colleagues compiled a list of resources for students to research prior to the discussion. Categories included historical context, current events and politics/democracy. Dupuis then had a class in which they reviewed pluralism, which is the idea that two differing opinions can coexist, before collectively brainstorming questions to answer together.

The following class was the discussion. It was structured with a silent reflection time to answer questions on your own first, and then a ‘fish bowl’ style conversation where 5 students discuss in an inner circle while the rest of the class sits quietly outside the circle until they decide to take the place of those that are talking.

Dupuis said the conversation went well.

“Students were engaged and leaning in,” Dupuis said. “Some people may have been really frustrated, a few people were really uncomfortable, [however], students were really respectful of each other without question.”

The results from an anonymous reflection survey the students filled out afterwards said that everyone who participated felt prepared and that the resources were beneficial, 3 out of 22 people said they were uncomfortable and 20 out of 22 people said they were glad the discussion happened.

“I think people really stepped up their maturity levels for the conversation and didn’t give too many biased opinions,” Iris Lord ‘26 said. “I think Ms. Dupuis did a really good job facilitating it in a way that kept people from getting loud and intimidating, but allowed people to disagree.”

Dupuis says the discussion came at the cost of not getting to some of the other belief systems in the curriculum, but the students were fine with making space for this, and she felt it was more important.

English 9 teacher Jory Hearst has not brought up the conflict to her classes.

“I feel cowardly about this because I’m so worked up and charged and have so many emotions that it’s overwhelming to think about staying professional,” Hearst said. “[But] I do think it’s our job as educators to make space for that and to help students understand.”

Loy Prussack is a student at Scripps College in California, and a BHS graduate. She is a leader of Students for Justice in Palestine and Jewish Voice for Peace. Prussack says it’s easier to have these types of conversations in college as opposed to high school. Still, it was a high school social studies teacher that first sparked her interest in advocacy when they showed a video about Gaza in her freshman year.

“My hope would be that all teachers are able to have discussion spaces even if they are spaces that are uncomfortable,” Prussack said. “Because I think it is adults’ responsibility to be holding those spaces as educators.”